On an unassuming plot of land, spitting distance from the train tracks that run through the center of Watts, you'll find one of the most stunning and improbable works of public art anywhere in the United States. Seventeen sculptures rise like giant, inverted ice cream cones toward the sky. The openwork spires are embedded with shells, tiles, soda bottles, mirrors, shards of pottery and two grinding wheels. It remains an island of whimsy in the middle of an urban landscape.

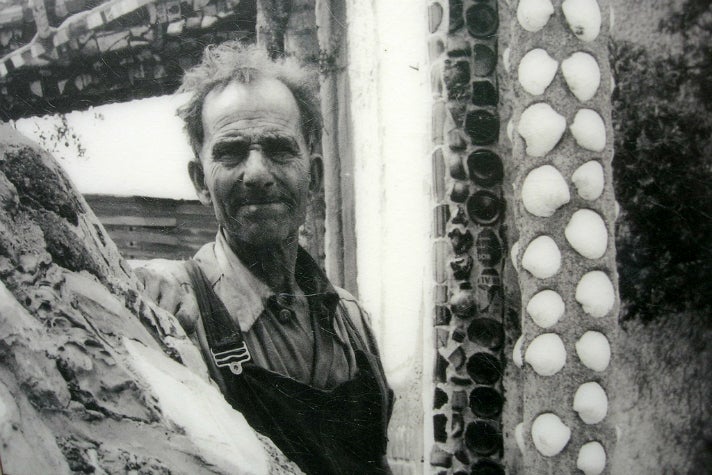

The Watts Towers are more remarkable when you know they were the vision of one man, a semi-literate Italian immigrant who worked, with no outside help and only the most elemental tools, nearly every day for 34 years to build a monument at once impenetrably personal and joyously communal.

The Backstory

He was born Sabato Rodia on February 12, 1879 in the tiny village of Ribottoli on the southwestern side of Italy. At age 15, he sailed for America. He settled in Philadelphia, then Seattle, then Northern California before moving to Southern California. He adopted the name Sam and worked as a laborer, laying cement and tile, among other things. Rodia was known as a hot-tempered man - something of a crank, complaining often about the government, the Catholic Church, the behavior of children, women who wore too much makeup. He may also have been a drunk.

Work Begins

In 1921, with help from his brother, Rodia bought an oddly shaped, triangular lot at 1765 E. 107th Street. Back then, Watts was its own city - it would vote to become part of L.A. in 1926. With his third wife, Carmen, Rodia moved into the small house on the property, the last lot on a dead-end street. Located next to a railroad, it was loud and dusty with streetcars and freight trains rumbling past several times a day. At age 42, Rodia began working on his masterpiece. Every day after work and all through the weekends, he would search for usable material and work, work, work. Carmen soon left him; according to Rodia, it was due to his obsession with the project.

The Man Without A Plan

To say that the Watts Towers were built without a vision would be wildly incorrect. But they were built without any plans, drawings or permits. They sprung from the mind of Rodia and his driving need, never truly explained by anyone, least of all himself. Over the years, Rodia (whose name was misspelled a gazillion different ways, most often as "Simon Rodilla") gave various answers when asked why he had expended so much effort to build the towers. Because it kept him away from drinking. Because he had lost his job. Because the people of the United States were nice. Because his wife was buried under the tallest tower. Because he wanted to do something big.

If You Build It...

Although he lacked formal schooling, Rodia's years as a laborer and his natural ingenuity led him to develop a unique method for building his dream structure on a limited budget and with few tools. He bent salvaged steel into the shapes he desired, wrapped wire mesh around it and covered it with thin layers of cement mortar. Since Rodia didn't have scaffolding, he laid out most of the elements he needed on the ground, carried them up in buckets along with his tools and assembled them in place. As he worked, he was anchored only by a window-washer's belt and buckle. An innovator in the use of thin-shell concrete, Rodia never stopped strengthening the structures, especially after the Long Beach earthquake of 1933. He was perpetually adding columns and connected concentric circles to each tower. Rodia was also mercurial, changing his mind while he worked, tearing down and rebuilding pinnacles when they didn't live up to his vision. The result was three tall spires and more than a dozen other sculptures, including a gazebo and the "Ship of Marco Polo."

...They Will Come

The Watts Towers were already a favorite among locals — jazz musician Charles Mingus, born in 1922 and raised in the shadow of the towers, was among many who drew inspiration from them — when they started getting attention from the wider world. Watts became a predominantly black neighborhood in the 1940s, in large part because African Americans were prevented from living in many other areas by racist housing covenants. The Watts Towers became a symbol of pride for the often neglected and under-resourced neighborhood. When much of the area was destroyed during the Watts Riots in 1965, the towers were miraculously unharmed. The towers appear on the covers of albums by Harold Land, Don Cherry and Tyrese. (Rodia himself is one of the many faces on The Beatles Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, next to Bob Dylan.)

Embedded In History

Look at the Watts Towers and you'll find bits of classic California pottery and ceramics dotting the structures. In addition to strengthening the columns, they provide eye-candy and a visual history of early 20th century California design. The Watts Towers are known to include are tiles from Malibu Potteries and Batchelder as well as dishware from Fiesta, Harlequin and probably Bauer and Metlox. All of these were local companies who helped shape the colorful, functional Craftsman aesthetic.

Laying Down His Tools

Just as no one quite knew why Rodia had begun his work, no one knew why he stopped. One day in 1955, he deeded the property to his neighbor and hopped on a bus to Northern California, to be near his sister's family. Rodia was 76 years old and had spent 34 years, nearly half his life, building the Watts Towers. He would die 10 years later, a month before the Watts Riots.

Structurally Sound

The tallest of the towers, known as the West Tower, is 99.5 feet or nearly ten stories high. In the 1950s, city officials decided the structures were unsafe and ordered them demolished. The L.A. art community mobilized to save them and convinced officials to perform a stress test in 1959. A steel cable was attached to each tower and connected to a crane exerted 10,000 pounds of lateral force. When the towers didn't budge, the city was forced to declare the Watts Towers structurally sound and lift the demolition order. Public tours of the property began in 1960.

Cultural Legacy & Preservation

The Watts Towers are exemplars of folk art and outsider art, terms for unclassifiable works of great originality or beauty created by the disenfranchised. But like Salvation Mountain near the Salton Sea or Harvey Fite's immersive sculpture Opus 40, the Watts Towers aren't easy to maintain. In fact, they're among the most threatened works of landscape art in the country, according to the Cultural Landscape Foundation. In 2010, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) formed a partnership with the City of Los Angeles, which manages the site, to preserve the Watts Towers.

The Watts Towers were added to the National Register of Historic Places in April 1977. The towers were designated a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument in March 1963, a California Historical Landmark in August 1990, and a U.S. National Historic Landmark in December 1990.

Getting There

The towers are a 10-minute walk from the 103rd Street / Watts Towers Station on the Metro Blue Line. Since everything is outdoors, you can show up any time to view the site. But it's surrounded by a fence and a locked gate, so if you want to step inside for a closer look at the cactus garden, the ship-shaped sculpture and other elements, you'll need to visit Thursday through Sunday and pay $7 for a guided tour.